At a Glance: South Carolina Mariculture

Past the bustling raw bars of downtown Charleston, and beyond the sway of oak tree branches shrouded in Spanish moss lie the great expanse of South Carolina's lush salt marshes and vast tidal areas. Below the surface exists a rich, symbiotic marine environment abundant in over 120 different species of organisms, including the oyster, a resilient symbol of Lowcountry culture and heritage that has been harvested for thousands of years. South Carolina's flat coastline, vast tidal areas and natural oyster reefs, combined with a lengthy spawning season, make the perfect habitat for growing meaty, briny oysters. Although top-culture commercial oyster farming is still relatively new to South Carolina, the state's relationship with the harvesting and consumption of oysters dates back thousands of years.

South Carolina's Coastal Environment is Perfect for Oysters

South Carolina boasts 344,500 acres of salt marsh, the most of any state on the east coast. In fact, the salt marshes of South Carolina comprise 20% of the salt marshes found on the East Coast.[1] The salt marsh is extremely valuable to South Carolina's economy. Three-quarters of the animals harvested as seafood in the state, even offshore species such as some groupers, spend all or part of their lives in estuarine waters around salt marshes.[2]

A variety of algae inhabits the salt marsh and serve as primary producers of food. Further, smooth cord grass, often called by its generic name, spartina, has evolved the ability to withstand regular inundation by saltwater. Instead, the grass dies back each fall and bacteria decompose it into a rich soup known as detritus that, along with algae, serves as the basis of the productive nutrient-rich salt marsh food web.[3]

Marshes are a highly important environment to the South Carolina ecosystem for a number of reasons.

First, they provide productive nursery grounds for numerous commercially and recreationally important species.

Second, they serve as filters to remove sediments and toxins from the water.

Third, marshes also buffer the mainland by slowing and absorbing storm surges, thereby reducing erosion of the coastline.[4]

Finally, when salt and fresh water combine in estuaries, they create an optimal natural environment for the growth of oysters. Check along a salt marsh edge, and you'll find clusters of oysters forming reefs. These reefs, in turn, serve as natural breakwaters and stabilize the shorelines.

Intertidal oysters are also found in groups known as oyster reefs. Oyster reefs are formed by oysters growing on a firm foundation of dead shells. Successive sets occur, joining clusters together to form a continuous group. The intricate, three-dimensional nature of oyster reefs provides extensive habitat for over 120 different marine species.[5] Mud crabs, shrimps, juvenile fishes and other organisms have been observed to seek shelter in reefs from predators as the tide rises. Loose oyster shell on creek bottoms serves as hard clam habitat as well as substrate for sponges, sea fans, and whip corals which, in turn, supply habitat for small crustaceans and fish.

A Lowcountry History: Wild Oysters Harvests

Native Americans who once inhabited South Carolina's Sea Islands 4,000 years ago loved oysters, their ardor made apparent by the massive middens of shucked shells they left behind. Early settlers made good use of the refuse, baking the shells to extract lime then mixing it with sand, oyster shells, and water to create a type of concrete called tabby. Able to withstand the elements, it was used in the building of houses and other structures, some of which are still standing.[6] Examples can be seen at the Tabby Ruins, a former slave home on Daufuskie Island, St. Helena's Chapel of Ease, Hilton Head's Drayton Hall Plantation, and the Tabby Manse in Beaufort, home to the most tabby structures in the nation.

Beyond their use as a building material, some of the first European settlers recognized the value of the potential oyster harvest and requested grants, from English kings and later provincial governments, to control shellfish grounds. In fact in the 18th century, present-day Charleston was known colloquially as "Oyster Point."[7]

Oysters were the most valuable South Carolina fishery from the late 1880s until just after World War II, according to “The Oyster Industry in South Carolina,” a report written by Victor G. Burrell, Jr. in 2003.[8] Burrell's report indicates that raw bars were in operation prior to the civil war. Further, in 1902, oysters accounted for 45% of the value of all South Carolina seafood harvested.[9] Harvesting and processing operations provided jobs even during the Great Depression when jobs were scarce.

Between 1865 and 1900, the oyster industry grew exponentially. At first, oysters were eaten locally, but when ice became available, commercial firms were formed that sold oysters raw and as shell stock to small cities in South Carolina and beyond.[10] In fact, an oyster company headquartered at 21 Bee Street in Charleston sold whole oysters, shucked meats, and steamed oysters from 1869-1871 to 59 different businesses, some as far away as New York City.[11]

Waterfront shucking houses and canneries were large operations, employing thousands of individuals. Documents compiled by Burrell indicate 11 canneries and 31 shucking houses were operating in the state in 1926. As recently as 1985, there were 12 shucking houses in the state. But wage and employment laws, stricter permitting, and fewer healthy oyster beds made it increasingly difficult to make a profit shucking and canning oysters. The last of the large canneries in the state, run by the Maggioni family on Lady’s Island, shut down in 1986.

The Rise of Mariculture

Mariculture is defined as the controlled cultivation in confinement of marine and estuarine organisms in salt water.[12]

Mariculture is not a brand new industry to South Carolina. The first oyster farm was permitted in 1840 near Sullivans Island. The first floating farm was permitted in 2013 to Lady's Island Oyster Company in Beaufort County.[13] Currently, there are 11 water column oyster permits comprising 88.9 acres of water in South Carolina, as well as a number of seafood businesses that commercially harvest wild oysters.[14]

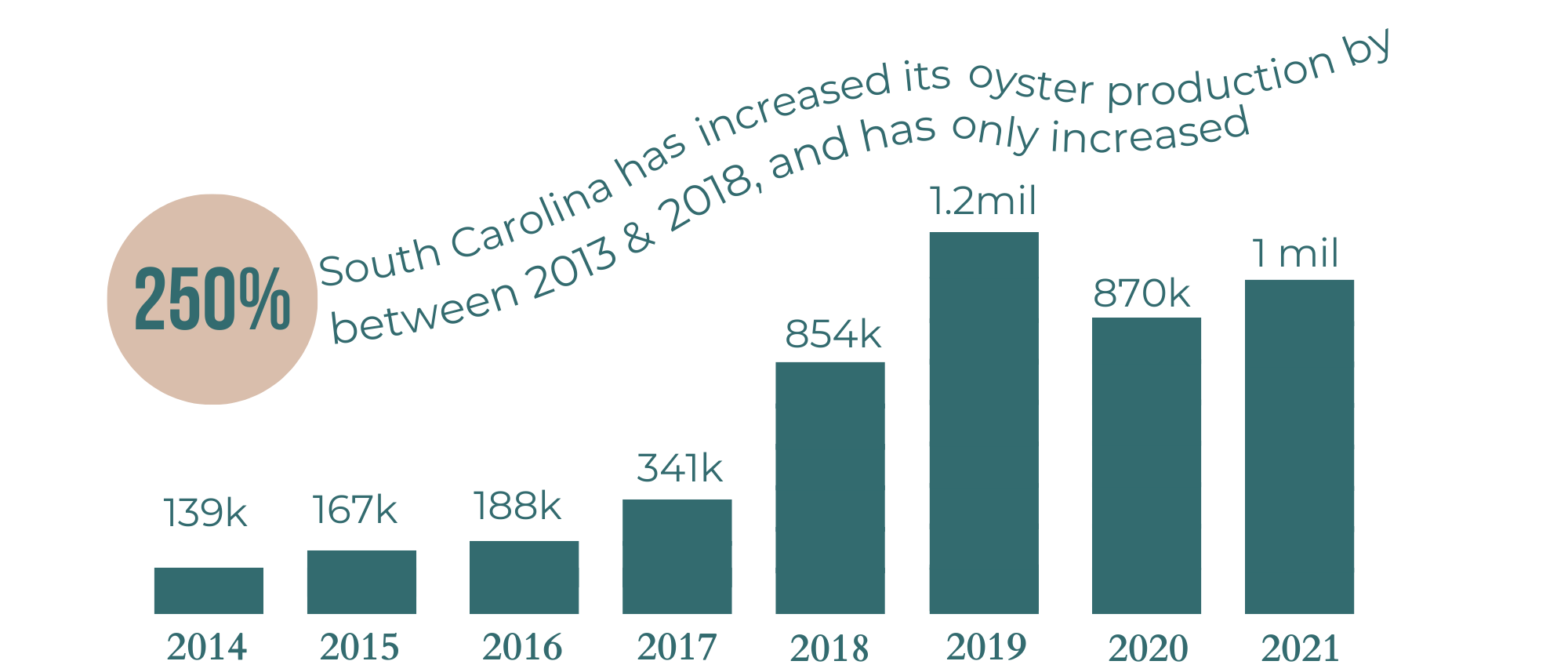

According to data from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, the amount of farmed oysters in South Carolina grew from 139,178 in 2014 to over 1,200,000 in 2019.[15]

In South Carolina, the oyster farm permitting process requires approval by three governmental agencies before a lease is granted: the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR), the OCRM, and the Army Corps of Engineers. The process, from start to finish, takes approximately two years. Applicants must complete physical paperwork and well as, oftentimes, in-person interviews about their proposed operations.

Lowcountry Mariculture Rules and Regulations

The Mariculture Rules and Regulations in South Carolina are governed by Section 50-5-900 et seq. Key requirements of commercial oyster farms in South Carolina are as follows:

Farms cannot exceed an aggregate of 500 bottom acres or an aggregate of 100 surface acres;[16]

In exercising its discretion of whether to grant an aquaculture permit, the SCDNR is allowed to consider the applicant's previous performance and compliance in natural resource laws;[17]

A commercial aquaculture permit is valid for 5 years;[18]

Applicants granted a license must submit a sworn statement stating the permittee has a wholesale dealer's license, a molluscan shellfish license, and a shellfish facility certified by the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Alternatively, the permittee must certify that all shellfish harvested for sale shall be handled through a wholesale dealer.[19]

In addition to commercial mariculture, the recreational harvesting of oysters and clams by individuals for personal consumption is a popular and traditional activity in South Carolina. In South Carolina, there are areas designated as Public Oyster Grounds—areas where South Carolina residents can gather oysters and clams for their personal use. Commercial harvesting is not permitted in designated Public Oyster Grounds. Currently, there are 21 public shellfish grounds and 13 state shellfish grounds managed exclusively for recreational harvesting.[20]

The recreational harvest season begins 30 minutes before the official sunrise on October 1, 2023, and runs through May 15, 2024. The SCDNR has maps which designate harvest areas, and are updated to consider shellfish area closures. Recreational harvests are limited to two bushels of oysters and one-half bushel of clams (a bushel is equivalent to 8 gallons). Harvesters must have a saltwater recreational fishing license.[21]

South Carolina Oyster Consumer Trends

According to the U.S. Census of Aquaculture, South Carolina has increased its production of oysters by more than 250% between 2013 and 2018.[22] This growth continued after 2018, with a recent study indicating an 84% increase through 2019.[23]

In 2020, a cohort of individuals from South Carolina Sea Grant and Clemson University conducted an empirical analysis of seafood preferences, consumption trends, and perception of aquaculture products amongst South Carolina residents.[24] The study was conducted via online survey distributed to random households across 46 counties in South Carolina. A total of 1,947 residents participated in the survey. I've included a link to the full analysis of the survey results here, but want to highlight some key finds as they pertain to oysters:

Seafood consumers in each county across South Carolina tended to by younger, female, well-educated, and long-term state residents. The average age of respondents was just under 44 years old, and a majority, 69%, were female;[25]

7% (or approximately 136 out of 1,947 participants) identified as being oyster consumers;

The biggest factors impacting whether a participant consumed oysters included: seasonality and locality;

While most fish species were consumed equally across seasons, oyster, crab, and shrimp consumption varied seasonally. Oyster consumption increased during winter months and crab and shrimp consumption increased during summer months;[26]

In South Carolina, the production method (i.e., wild harvest vs capture fisheries vs aquaculture) and proximity of oyster cultivation to consumers are important considerations in consumer valuation and willingness to pay for a product;

Preference for local seafood and aquaculture products is a reoccurring interest that consumers have continued to show when making food purchases;[27]

Studies found that South Carolina residents’ ratings of importance for the attributes “environmentally sustainable,” “wild-caught,” and “harvested locally” were significantly higher than tourist ratings for the same attributes;[28]

It is estimated that in South Carolina, an excess of 90% of farm-raised oysters are sold directly to restaurants where they are marketed as half-shell quality, which further explains the demand for out-of-home consumption of certain aquaculture products.

Upon the success of the 2021 Seafood Consumption study, a follow-up study focused exclusively on oysters was conducted in 2022.[29] This study was conducted, in part, to provide marketing data to South Carolina oyster producers are looking to expand into other sales channels. Again, a link to a full analysis of the study can be found here. Some key highlights are as follows:

The results indicate South Carolina oyster consumers tend to be younger, Caucasian, live in coastal counties, have higher household incomes, and prefer eating oysters at restaurants.

Consumers willing to pay higher prices for oysters to eat at home tend to be younger, female, have higher household incomes, and are not Caucasian;

Restaurants are the most common locations for eating oysters (74.7%), followed by home (44.5%) and roasts (40.6%);

The top 3 reasons preventing consumers from buying more oysters at restaurants included: availability, price, and food safety concerns;

The preferred preparation methods ranged from steamed (70.9%), followed by grilled (48.4%), raw (41.9%), and cooked in a recipe with other ingredients (33.4%);

The barriers preventing survey participants from purchasing more oysters included: availability of fresh oysters (48%) and price (48%). Another factor most cited included desiring oysters that were pre-shucked (38.4%);

A sizable portion of consumers felt like local oysters were "over-priced" at local restaurants (which were priced between $2.00 and $3.50 at area restaurants).

Lowcountry Oyster Trail

The Lowcountry Oyster Trail is a new aquatourism initiative that officially launched in 2017. The trial highlights the region's legendary oysters, as well as the growing culinary movement which in turns promotes economic development, and environmental initiative to promote and enhance marine ecological research, analysis, and environmental stewardship for the region.

Oyster Shell Recycling

Although South Carolina's commercial shellfish harvest has remained stable over the past three decades, the closing of oyster canneries and most shucking houses during this period has resulted in a shortage of shucked oyster shell needed to cultivate and restore oyster beds. The increasing popularity of backyard oyster roasts and by-the-bushel retail sales have contributed to this shortage in that, contrary to the shucking houses and canneries, shells remaining from individual oyster roasts are not usually returned to the estuary to provide a suitable surface to attract juvenile oysters. More often than not, the shell ends up in driveways and landfills.

These factors have contributed to the critical shortage of oyster shell used for planting purposes and sustaining oyster habitat. The state has been forced to purchase the majority of its oyster shell from out-of-state processors to supplement our stocks of shell for planting. In order for SCDNR to properly manage the state's shellfish resources and maintain these critical habitats, we must continue to maximize our efforts to recycle our oyster shells. Recycling your shells will help restore, preserve, and enhance the state's inshore marine habitat.

South Carolina Oyster Farms & Operations

Gullah Oyster Man

Citations

[1] South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Marine – Salt Marsh Habitat, available at www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/habitat/saltmarsh.html

[2] South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Dynamics of the Salt Marsh, available at www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/pub/seascience/dynamic.html

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Sea Science: An Information / Education Series from the Marine Resource Division, available at www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/pub/seascience/oyster.html

[6] Wiersema, Libby, All About South Carolina Oysters, available at https://discoversouthcarolina.com/articles

[7] Burrell, Victor G. Jr. The Oyster Industry in South Carolina, pg 1 available at Oyster Industry in SC tif (archive.org).

[8] Id.

[9] Id at 1.

[10] Id at 6

[11] Id at 6.

[12] S.C. Code Section 44-1-140 (A)(2)(jj)

[13] South Carolina Shellfish Growers Association available at https://scshellfishgrowers.org/about/

[14] South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Marine-Shellfish Mariculture, available at www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/shellfish/mariculture.html

[15] South Carolina Shellfish: Farming Oysters to Meet Southern Demands, available at https://mountpleasantmagazine.com/2021/things/

[16] Section 50-5-900(A)

[17] Id.

[18] Section 50-5-900(B)

[19] Section 50-5-910 (C)

[20] South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, South Carolina shellfish harvest season opens October 1, September 20, 2023, availbale at www.dnr.sc.gov/news

[21] South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Marine-Shellfish: Recreational Harvest, available at www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/shellfish/regs.html

[22] (USDA, 2019)

[23] South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium, 2021. This increase was mostly due to the adoption of new oyster farming technology—floating cages—which keep oysters in ideal water temperature, salinity, and nutrient content (Holleman, 2018)

[24] Seafood Consumption Preferences and Attributes Influencing Awareness of South Carolina Aquaculture Practices, Journal of Food Distribution Research Volume 52, Issue 3, pp 24-45.

[25] Id at pp 30.

[26] The increase in consumption of oysters in winter months can be attributed partly to consumers’ concern about eating oysters during summer months when water temperature is higher, which can increase the risk of shellfish poisoning due to pathogens such as Vibrio spp. (Børresen, 2009).

[27] Grebitus, Lusk, and Nayga, 2013; Chen et al., 2017

[28] Jodice and Norman (2020)

[29] Factors Affecting Consumer Purchasing Decisions and Willingness to Pay for Oysters in South Carolina, Journal of Food Distribution Research Volume 53 Issue 2, pp 1-25, available at JFDR53.2_1_Richards.pdf (fdrsinc.org)